Belfast

City of Belfast

| |

|---|---|

| Motto(s): | |

| Coordinates: 54°35′47″N 05°55′48″W / 54.59639°N 5.93000°W | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Northern Ireland |

| Incorporated | 1 April 2015 |

| Administrative HQ | City Hall |

| Government | |

| • Type | District council |

| • Body | Belfast City Council |

| • Executive | Committee system |

| • Control | No overall control |

| • MPs | 4 MPs |

| • MLAs | |

| Area | |

• Total | 51 sq mi (133 km2) |

| • Rank | 11th |

| Population (2022)[2] | |

• Total | 348,005 |

| • Rank | 1st |

| • Density | 6,780/sq mi (2,617/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC+0 (GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

| Postcode areas |

|

| Dialling codes | 028 |

| ISO 3166 code | GB-BFS |

| GSS code | N09000003 |

| Website | belfastcity |

Belfast (/ˈbɛlfæst/ ⓘ, BEL-fast, /-fɑːst/, -fahst;[a] from Irish: Béal Feirste [bʲeːlˠ ˈfʲɛɾˠ(ə)ʃtʲə]ⓘ)[3][4] is the capital city and principal port of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan and connected to the open sea through Belfast Lough and the North Channel. It is the second-largest city on the island of Ireland (after Dublin), with an estimated population of 348,005 in 2022,[2] and a metropolitan area population of 671,559.[5]

First chartered as an English settlement in 1613, the town's early growth was driven by an influx of Scottish Presbyterians. Their descendants' disaffection with Ireland's Anglican establishment contributed to the rebellion of 1798, and to the union with Great Britain in 1800 — later regarded as a key to the town's industrial transformation. When granted city status in 1888, Belfast was the world's largest centre of linen manufacture, and by the 1900s her shipyards were building up to a quarter of total United Kingdom tonnage.

Sectarian tensions accompanied the growth of an Irish Catholic population drawn by mill and factory employment from western districts. Heightened by division over Ireland's future in the United Kingdom, these twice erupted in periods of sustained violence: in 1920–22, as Belfast emerged as the capital of the six northeast counties retaining the British connection, and over three decades from the late 1960s during which the British Army was continually deployed on the streets. A legacy of conflict is the barrier-reinforced separation of Protestant and Catholic working-class districts.

Since the Good Friday Agreement, the electoral balance in the once unionist-controlled city has shifted, albeit with no overall majority, in favour of Irish nationalists. At the same time, new immigrants are adding to the growing number of residents unwilling to identify with either of the two communal traditions.

Belfast has seen significant services sector growth, with important contributions from financial technology (fintech), from tourism and, with facilities in the redeveloped Harbour Estate, from film. It retains a port with commercial and industrial docks, including a reduced Harland & Wolff shipyard and aerospace and defence contractors. Post Brexit, Belfast and Northern Ireland remain, uniquely, within both the British domestic and European Single trading areas for goods.

The city is served by two airports: George Best Belfast City Airport on the Lough shore and Belfast International Airport 15 miles (24 kilometres) west of the city. It supports two universities: on the north-side of the city centre, Ulster University, and on the southside the longer established Queens University. Since 2021, Belfast has been a UNESCO designated City of Music.

History

[edit]Name

[edit]

The name Belfast derives from the Irish Béal Feirste (Irish pronunciation: [bʲeːlˠ ˈfʲɛɾˠ(ə)ʃtʲə]),[4] "Mouth of the Farset"[6] a river whose name in the Irish, Feirste, refers to a sandbar or tidal ford.[7] This was formed where the river ran—until culverted late in the 18th century, down High Street—[8] into the Lagan. It was at this crossing, located under or close to the current Queen's Bridge, that the early settlement developed.[9]: 74–77

The compilers of Ulster-Scots use various transcriptions of local pronunciations of "Belfast" (with which they sometimes are also content)[10][11] including Bilfawst,[12][13] Bilfaust[14] or Baelfawst.[15]

Early settlements

[edit]The site of Belfast has been occupied since the Bronze Age. The Giant's Ring, a 5,000-year-old henge, is located near the city,[9]: 42–45 [16] and the remains of Iron Age hill forts can still be seen in the surrounding hills. At the beginning of the 14th century, Papal tax rolls record two churches: the "Chapel of Dundela" at Knock (Irish: cnoc, meaning "hill") in the east,[17] connected by some accounts to the 7th-century evangelist St. Colmcille,[18]: 11 and, the "Chapel of the Ford", which may have been a successor to a much older parish church on the present Shankill (Seanchill, "Old Church") Road,[9]: 63–64 dating back to the 9th,[19] and possibly to St. Patrick in the mid 5th, century.[20]

A Norman settlement at the ford, comprising the parish church (now St. George's), a watermill, and a small fort,[21] was an outpost of Carrickfergus Castle. Established in the late 12th century, 11 miles (18 km) out along the north shore of the Lough, Carrickfergus was to remain the principal English foothold in the north-east until the scorched- earth Nine Years' War at the end of the 16th century broke the remaining Irish power, the O'Neills.[22]

Developing port, radical politics

[edit]With a commission from James I, in 1613 Sir Arthur Chichester undertook the Plantation of Belfast and the surrounding area, attracting mainly English and Manx settlers.[23] The subsequent arrival of Scottish Presbyterians embroiled Belfast in its only recorded siege: denounced from London by John Milton as "ungrateful and treacherous guests",[24] in 1649 the newcomers were temporarily expelled by an English Parliamentarian army.[25]: 21 [26] In 1689, Catholic Jacobite forces, briefly in command of the town,[27] abandoned it in advance of the landing at Carrickfergus of William, Prince of Orange, who proceeded through the Belfast to his celebrated victory on 12 July 1690 at the Boyne.[28]

Together with French Huguenots, the Scots introduced the production of linen, a flax-spinning industry that in the 18th century carried Belfast trade to the Americas.[29] Fortunes were made carrying rough linen clothing and salted provisions to the slave plantations of the West Indies; sugar and rum to Baltimore and New York; and for the return to Belfast flaxseed and tobacco from the colonies.[30] From the 1760s, profits from the trade financed improvements in the town's commercial infrastructure, including the Lagan Canal, new docks and quays, and the construction of the White Linen Hall which together attracted to Belfast the linen trade that had formerly gone through Dublin. Abolitionist sentiment, however, defeated the proposal of the greatest of the merchant houses, Cunningham and Greg, in 1786 to commission ships for the Middle Passage.[31]

As "Dissenters" from the established Anglican church (with its episcopacy and ritual), Presbyterians were conscious of sharing, if only in part, the disabilities of Ireland's dispossessed Roman Catholic majority; and of being denied representation in the Irish Parliament. Belfast's two MPs remained nominees of the Chichesters (Marquesses of Donegall). With their emigrant kinsmen in America, the region's Presbyterians were to share a growing disaffection from the Crown.[32]: 55–61 [33]

When early in the American War of Independence, Belfast Lough was raided by the privateer John Paul Jones, the townspeople assembled their own Volunteer militia. Formed ostensibly for defence of the Kingdom, Volunteer corps were soon pressing their own protest against "taxation without representation". Further emboldened by the French Revolution, a more radical element in the town, the Society of United Irishmen, called for Catholic emancipation and a representative national government.[34] In hopes of French assistance, in 1798 the Society organised a republican insurrection. The rebel tradesmen and tenant farmers were defeated north of the town at the Battle of Antrim and to the south at the Battle of Ballynahinch.[35]

Britain seized on the rebellion to abolish the Irish Parliament, unlamented in Belfast, and to incorporate Ireland in a United Kingdom.[36] In 1832, British parliamentary reform permitted the town its first electoral contest[37] – an occasion for an early and lethal sectarian riot.[38]: 87

Industrial expansion, sectarian division

[edit]

While other Irish towns experienced a loss of manufacturing, from the 1820s Belfast underwent rapid industrial expansion. After a cotton boom and bust, the town emerged as the global leader in the production of linen goods (mill, and finishing, work largely employing women and children),[39] winning the moniker "Linenopolis".[40] Shipbuilding led the development of heavier industry.[41] By the 1900s, her shipyards were building up to a quarter of the total United Kingdom tonnage.[42] This included from the yard of Harland & Wolff the ill-fated RMS Titanic, at the time of her launch in 1911 the largest ship afloat.[43] Other major export industries included textile machinery, rope, tobacco and mineral waters.[18]: 59–88

Industry drew in a new Catholic population settling largely in the west of the town—refugees from a rural poverty intensified by Belfast's mechanisation of spinning and weaving and, in the 1840s, by famine.[44] The plentiful supply of cheap labour helped attract English and Scottish capital to Belfast, but it was also a cause of insecurity.[45] Protestant workers organised and dominated the apprenticed trades[46] and gave a new lease of life to the once largely rural Orange Order.[47][48] Sectarian tensions, which frequently broke out in riots and workplace expulsions, were also driven by the "constitutional question": the prospect of a restored Irish parliament in which Protestants (and northern industry) feared being a minority interest.[46]

On 28 September 1912, unionists massed at Belfast's City Hall to sign the Ulster Covenant, pledging to use "all means which may be found necessary to defeat the present conspiracy to set up a Home Rule Parliament in Ireland".[49] This was followed by the drilling and eventual arming of a 100,000-strong Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF).[50] The immediate crisis was averted by the onset of the Great War. The UVF formed the 36th (Ulster) Division whose sacrifices in the Battle of the Somme continue to be commemorated in the city by unionist and loyalist organisations.[51]

In 1920–22, as Belfast emerged as the capital of the six counties remaining as Northern Ireland in the United Kingdom, there was widespread violence. 8,000 "disloyal" workers were driven from their jobs in the shipyards:[52] in addition to Catholics, "rotten Prods" – Protestants whose labour politics disregarded sectarian distinctions.[53]: 104–108 Gun battles, grenade attacks and house burnings contributed to as many as 500 deaths.[54] A curfew remained in force until 1924.[55] (see The Troubles in Ulster (1920–1922)) The lines drawn saw off the challenge to "unionist unity" posed by labour (industry had been paralysed by strikes in 1907 and again in 1919).[56] Until "troubles" returned at the end of the 1960s, it was not uncommon in Belfast for the Ulster Unionist Party to have its council and parliamentary candidates returned unopposed.[57][58]

In 1932, the opening of the new buildings for Northern Ireland's devolved Parliament at Stormont[59] was overshadowed by the protests of the unemployed and ten days of running street battles with the police. The government conceded increases in Outdoor Relief, but labour unity was short lived.[38]: 219–220 In 1935, celebrations of King George V's Jubilee and of the annual Twelfth were followed by deadly riots and expulsions, a sectarian logic that extended itself to the interpretation of darkening events in Europe.[38]: 226–233 Labour candidates found their support for the anti-clerical Spanish Republic characterised as another instance of No-Popery.[60] (Today, the cause of the republic in the Spanish Civil War is commemorated by a "No Pasaran" stained glass window in City Hall).[61]

In 1938, nearly a third of industrial workers were unemployed, malnutrition was a major issue, and at 9.6% the city's infant mortality rate (compared with 5.9% in Sheffield, England) was among the highest in United Kingdom.[62]

The Blitz and post-war development

[edit]

In the spring of 1941, the German Luftwaffe appeared twice over Belfast. In addition to the shipyards and the Short & Harland aircraft factory, the Belfast Blitz severely damaged or destroyed more than half the city's housing stock, and devastated the old town centre around High Street.[63] In the greatest loss of life in any air raid outside of London, more than a thousand people were killed.[64]

At the end of World War II, the Unionist government undertook programmes of "slum clearance" (the Blitz had exposed the "uninhabitable" condition of much of the city's housing) which involved decanting populations out of mill and factory built red-brick terraces and into new peripheral housing estates.[65][66] At the same time, a British-funded welfare state "revolutionised access" to education and health care.[67] The resulting rise in expectations; together with the uncertainty caused by the decline of the city's Victorian-era industries, contributed to growing protest, and counter protest, in the 1960s over the Unionist government's record on civil and political rights.[68]

The Troubles

[edit]For reasons that nationalists and unionists dispute,[69] the public protests of the late 1960s soon gave way to communal violence (in which as many as 60,000 people were intimidated from their homes)[70]: 70 and to loyalist and republican paramilitarism. Introduced onto the streets in August 1969, the British Army committed to the longest continuous deployment in its history, Operation Banner. Beginning in 1970 with the Falls curfew, and followed in 1971 by internment, this included counterinsurgency measures directed chiefly at the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) who characterised their operations, including the bombing of Belfast's commercial centre, as a struggle against British occupation.[71][72]

Preceded by loyalist and republican ceasefires, the 1998 "Good Friday" Belfast Agreement returned a new power-sharing legislative assembly and executive to Stormont.[73] In the intervening years in Belfast, some 20,000 people had been injured, and 1,500 killed.[70]: 73 [74]

Eighty-five percent of the conflict-related deaths had occurred within 1,000 metres of the communal interfaces, largely in the north and west of the city.[70]: 73 The security barriers erected at these interfaces are an enduring physical legacy of the Troubles.[75] The 14 neighbourhoods they separate are among the 20 most deprived wards in Northern Ireland.[76] In May 2013, the Northern Ireland Executive committed to the removal of all peace lines by mutual consent.[77][78] The target date of 2023 was passed with only a small number dismantled.[79][80]

The more affluent districts escaped the worst of the violence, but the city centre was a major target. This was especially so during the first phase of the PIRA campaign in the early 1970s, when the organisation hoped to secure quick political results through maximum destruction.[75]: 331–332 Including car bombs and incendiaries, between 1969 and 1977 the city experienced 2,280 explosions.[25]: 58 In addition to the death and injury caused, they accelerated the loss of the city's Victorian fabric.[81]

21st century

[edit]Since the turn of the century, the loss of employment and population in the city centre has been reversed.[82] This reflects the growth of the service economy, for which a new district has been developed on former dockland, the Titanic Quarter. The growing tourism sector paradoxically lists as attractions the murals and peace walls that echo the violence of the past.[75]: 350.352 In recent years, "Troubles tourism"[32]: 180–189 has presented visitors with new territorial markers: flags, murals and graffiti in which loyalists and republicans take opposing sides in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.[83]

The demographic balance of some areas has been changed by immigration (according to the 2021 census just under 10% of the city's population was born outside the British Isles),[84] by local differences in births and deaths between Catholics and Protestants, and by a growing number of, particularly younger, people no longer willing to self-identify on traditional lines.[66]

In 1997, unionists lost overall control of Belfast City Council for the first time in its history. The election in 2011 saw Irish nationalist councillors outnumber unionist councillors, with Sinn Féin becoming the largest party, and the cross-community Alliance Party holding the balance of power.[85]

In the 2016 Brexit referendum, Belfast's four parliamentary constituencies returned a substantial majority (60 percent) for remaining within the European Union, as did Northern Ireland as a whole (55.8), the only UK region outside London and Scotland to do so.[86] In February 2022, the Democratic Unionist Party, which had actively campaigned for Brexit, withdrew from the power-sharing executive and collapsed the Stormont institutions to protest the 2020 UK-EU Northern Ireland Protocol. With the promise of equal access to the British and European markets, this designates Belfast as a point of entry to the European Single Market within whose regulatory framework local producers will continue to operate.[87] After two years, the standoff was resolved with an agreement to eliminate routine checks on UK-destined goods.[88]

Cityscape

[edit]Location and topography

[edit]

Belfast is at the mouth of the River Lagan at the head of Belfast Lough open through the North Channel to the Irish Sea and to the North Atlantic. In the course of the 19th century, the location's estuarine features were re-engineered. With dredging and reclamation, the lough was made to accommodate a deep sea port, and extensive shipyards.[89] The Lagan was banked (in 1994 a weir raised its water level to cover what remained of the tidal mud flats)[90] and its various tributaries were culverted[91] On the model pioneered in 2008 by the Connswater Community Greenway some, including the course of the Farset, are now being considered for "daylighting".[92]

It remains the case that much of the city centre is built on an estuarine bed of "sleech": silt, peat, mud and—a source the city's ubiquitous red brick— soft clay, that presents a challenge for high-rise construction.[93] (In 2007 this soft foundation persuaded St Anne's Cathedral to abandon plans for a bell tower and substitute a lightweight steel spire).[94] The city centre is also subject to tidal flood risk. Rising sea levels could mean, that without significant investment, flooding in the coming decades will be persistent.[95]

The city is overlooked on the County Antrim side (to the north and northwest) by a precipitous basalt escarpment—the near continuous line of Divis Mountain (478 m), Black Mountain (389 m) and Cavehill (368 m)—whose "heathery slopes and hanging fields are visible from almost any part of the city".[89]: 13 From County Down side (on the south and south east) it is flanked by the lower-lying Castlereagh and Hollywood hills. The sand and gravel Malone Ridge extends up river to the south-west.

North Belfast and Shankill

[edit]From 1820, Belfast began to spread rapidly beyond its 18th century limits. To the north, it stretched out along roads which drew into the town migrants from Scots-settled hinterland of County Antrim.[45] Largely Presbyterian, they enveloped a number of Catholic-occupied "mill-row" clusters: New Lodge, Ardoyne and "the Marrowbone".[96][97] Together with areas of more substantial housing in the Oldpark district, these are wedged between Protestant working-class housing stretching from Tiger's Bay out the Shore Road on one side, and up the Shankill (the original Antrim Road) on the other.[98]

The Greater Shankill area, including Crumlin and Woodvale, is over the line from the Belfast North parliamentary/assembly constituency, but is physically separated from the rest of Belfast West by an extensive series of separation barriers[99]—peace walls—owned (together with five daytime gates into the Falls area) by the Department of Justice.[100] These include Cupar Way where tourists are informed that, at 45 feet, the barrier is "three times higher than the Berlin Wall and has been in place for twice as long".[101]

With other working-class districts, Shankill suffered from the "collapse of old industrial Belfast".[102] But it was also greatly affected from the 1960s by the city's most ambitious programme of "slum clearance". Red-brick, "two up, two down" terraced streets, typical of 19th century working-class housing, were replaced with flats, maisonettes, and car parks but few facilities. In a period of twenty years, due largely to redevelopment, 50,000 residents left the area leaving an aging population of 26,000[103][102] and more than 100 acres of wasteland.[104]

Meanwhile, road schemes, including the terminus of the M1 motorway and the Westlink, demolished a mixed dockland community, Sailortown, and severed the streets linking the Shankill area and the rest of both north and west Belfast to the city centre.[105][106]

New "green field" housing estates were built on the outer edges of the city. The onset of the Troubles overwhelmed attempts to promote these as "mixed" neighbourhoods so that the largest of these developments on the city's northern edge, Rathcoole, rapidly solidified as a loyalist community.[107] In 2004, it was estimated that 98% of public housing in Belfast was divided along religious lines.[108]

Among the principal landmarks of north Belfast are the Crumlin Road Gaol (1845) now a major visitor attraction, Belfast Royal Academy (1785) - the oldest school in the city, St Malachy's College (1833), Holy Cross Church, Ardoyne (1902), Waterworks Park (1889), and Belfast Zoo (1934).

West Belfast

[edit]In the mid-19th century rural poverty and famine drove large numbers of Catholic tenant farmers, landless labourers and their families toward Belfast. Their route brought them down the Falls Road and into what are now remnants of an older Catholic enclave around St Mary's Church, the town's first Catholic chapel (opened in 1784 with Presbyterian subscriptions),[109] and Smithfield Market.[45] Eventually, an entire west side of the city, stretching up the Falls Road, along the Springfield Road (encompassing the new housing estates built 1950s and 60s: Highfield, New Barnsley, Ballymurphy, Whiterock and Turf Lodge) and out past Andersonstown on the Stewartstown Road toward Poleglass, became near-exclusively Catholic and, in political terms, nationalist.

Reflecting the nature of available employment as mill workers, domestics and shop assistants, the population, initially, was disproportionately female. Further opportunities for women on the Falls Road arose through developments in education and public health. In 1900, the Dominican Order opened St Mary's [Teacher] Training College, and in 1903 King Edward VII opened the Royal Victoria Hospital at the junction with the Grosvenor Road.[110] Extensively redeveloped and expanded, the hospital has a staff of more than 8,500.[111]

Landmarks in the area include the Gothic-revival St Peter's Cathedral (1866, signature twin spires added in 1886);[112] Clonard Monastery (1911), the Conway Mill (1853/1901, re-developed as a community enterprise, arts and education centre in 1983);[113] Belfast City Cemetery (1869) and, best known for its republican graves, Milltown Cemetery (1869).

The area's greatest visitor attractions are its wall and gable-end murals. In contrast to those in loyalist areas, where Israel is typically the only outside reference, these range more freely beyond the local conflict frequently expressing solidarity with Palestinians, with Cuba, and with Basque and Catalan separatists.[114][115]

South Belfast

[edit]West Belfast is separated from South Belfast, and from the otherwise abutting loyalist districts of Sandy Row and the Donegall Road, by rail lines, the M1 Motorway (to Dublin and the west); industrial and retail parks, and the remnants of the Blackstaff (Owenvarra) bog meadows.

Belfast began stretching up-river in the 1840s and 50s: out the Ormeau and Lisburn roads and, between them, running along a ridge of higher ground, the Malone Road. From "leafy" avenues of increasingly substantial (and in the course of time "mixed") housing, the Upper Malone broadened out into areas of parkland and villas.

Further out still, where they did not survive as public parks, from the 1960s the great-house demesnes of the city's former mill-owners and industrialists were developed for public housing: loyalist estates such as Seymour Hill and Belvoir. Meanwhile, in Malone and along the river embankments, new houses and apartment blocks have been squeezed in, increasing the general housing density.[116]

Beyond the Queen's University area the area's principal landmarks are the 15-storey tower block of Belfast City Hospital (1986) on the Lisburn Road, and the Lagan Valley Regional Park through which a towpath extends from the City-centre quayside to Lisburn.[117]

Northern Ireland's three permanent diplomatic missions are situated on the Malone Road, the consulates of China,[118] Poland [119] and the United States.[120]

East Belfast

[edit]The first district on the right bank of the Lagan (the County Down side) to be incorporated in Belfast was Ballymacarrett after 1868.[38][121] Harland & Wolff, whose gantry cranes, Samson & Goliath, tower over the area, was long the mainstay of employment — although less securely so for the townland's Catholics (In 1970, when the yard still had a workforce of 10,000, only 400 Catholics were employed).[38]: 280 Tolerated in periods of expansion as navvies and casual labourers,[53]: 87–88 they concentrated in a small enclave, the Short Strand, which has continued into this century to feature as a sectarian flashpoint.[122][123] Home to around 2,500 people, it is the only distinctly nationalist area in the east of the river.[124]

East Belfast developed from the Queens Bridge (1843), through Ballymacarrett, east along the Newtownards Road and north (along the east shore of the Lough) up the Holywood Road; and from the Albert Bridge (1890) south east out the Cregagh and Castlereagh roads. The further out, the more substantial, and less religiously segregated, the housing until again encountering the city's outer ring of public housing estates: loyalist Knocknagoney, Lisnasharragh, and Tullycarnet.

This century, efforts have been made to add to East Belfast's two obvious visitor attractions: Samson & Goliath (the "banana yellow" Harland & Wolff cranes date only from the early 1970s)[53]: 79 and the Parliament Buildings at Stormont. What is marketed now as EastSide, features, at the intersection of the Connswater and Comber Greenways and next to the EastSide Visitor Centre, CS Lewis Square (2017), named and themed in honour of the local author of The Chronicles of Narnia.[125] Next to the former the Harland & Wolff Drawing Offices (now an hotel), stands the "cultural nucleus to Titanic Quarter", Titanic Belfast (2012) whose interactive galleries tell the liner's ill-fated story.[126]

City Centre

[edit]Belfast City Centre is roughly bounded by the ring roads constructed since the 1970s: the M3 which sweeps across the dockland to the north; the Westlink that connects to the M1 for points south and west; and, with less certainty, the Bruce Street and Bankmore connectors that tie back toward the Lagan at the Gasworks Business Park and the beginning of the Ormeau Road. This embraces "the Markets", the one remaining inner-city area of housing.[127] Of the various markets, including those for the sale and shipping of livestock, from which it derives its name, only one survives, the former produce market, St George's,[128] now a food and craft market popular with visitors to the city.[129]

Architectural heritage

[edit]

Among surviving elements of the pre-Victorian town are the Belfast Entries, 17th-century alleyways off High Street, including, in Winecellar Entry, White's Tavern (rebuilt 1790); the elliptical First Presbyterian (Non-Subscribing) Church (1781–83) in Rosemary Street (whose members led the abolitionist charge against Greg and Cunningham);[130] the Assembly Rooms (1769, 1776, 1845) on Bridge Street; St George's Church of Ireland (1816) on the High Street site of the old Corporation Church; St Mary's Church (1782) in Chapel Lane, which is the oldest Catholic church in the city. The oldest public building in Belfast, Clifton House (1771–74), the Belfast Charitable Society poorhouse, is on North Queen Street. It is now partly cut off from the city centre by arterial roads. In addition there are small sets of city-centre Georgian terraces.[131]

Of the much larger Victorian city a substantial legacy has survived the Blitz, The Troubles and planning and development. Among the more notable examples[131] are St Malachy's Roman Catholic Church (1844) and the original college building of Queen's University Belfast (1849), both in a Tudor style; the Palm House in the Botanic Gardens (1852); the Renaissance revival Union Theological College (1853) and Ulster Bank (now Merchant Hotel) (1860); the Italianate Ulster Hall (1862), and the National Trust restored ornate Crown Liquor Saloon (1885, 1898) (a setting for the classic film, Odd Man Out, starring James Mason);[132] the oriental-themed Grand Opera House (1895) (bombed several times during the Troubles),[133] and the Romanesque revival St. Patrick's Catholic Church in Donegall Street (1877).

The Baroque revival City Hall was finished in 1906 on the site of the former White Linen Hall, and was built to reflect Belfast's city status, granted by Queen Victoria in 1888. Its Edwardian design influenced the Victoria Memorial in Calcutta, India, and Durban City Hall in South Africa.[134][135] The dome is 173 ft (53 m) high and figures above the door state "Hibernia encouraging and promoting the Commerce and Arts of the City".[136]

Nearby is the Renaissance and Baroque revival Scottish Provident Institution (1902). Opposite is a branch of the Ulster Bank which is built behind the facade of a large former Methodist church which was built in the classical style and which opened in 1846.

Built around an older church dating to 1776, St Anne's Church of Ireland Cathedral was consecrated 1904 and completed in the 1920s. Its steel spire was added in 2007. The neoclassical Royal Courts of Justice were opened in 1933.

Redevelopment

[edit]The opening Victoria Square Shopping Centre in 2008 was to symbolise the rebound of the city centre since its days as a restricted security zone during the Troubles.[137] But retail footfall in the centre is limited by competition with out-of-town shopping centres and with internet retailing. As of November 2023, footfall had not recovered pre-COVID pandemic levels.[138] There are compensating trends: the growth in tourism and hospitality which has included a sustained boom in hotel construction.[139]

The City Council also talks of a "residential-led regeneration".[140][141] New townhouse and apartments schemes are being developed for the city's quays,[142] and for Titanic Quarter.[143] The completion in 2023 of Ulster University's enhanced Belfast campus (in "one of the largest higher education capital builds in Europe")[144] and the determination of Queen's University to compete with the private sector in the provision of student housing,[145] has fostered the construction downtown of multiple new student residences.[146]

Rough sleeping and homelessness

[edit]People can be found sleeping rough on the streets of the city centre. Numbers, while growing, may be comparatively small for a city of its size in the British Isles. In 2022, counts and estimates by the Northern Ireland Housing Executive identified a total of 26 rough sleepers in Belfast.[147] This is against a background (in 2023) of 2,317 people (0.67% of residents) presenting as homeless, many of whom are in temporary accommodation and shelters.[148] Such figures, however, do not include all those living in severely overcrowded conditions, involuntarily sharing with other households on a long-term basis, or sleeping rough in hidden locations.[149][150]

The "Quarters"

[edit]

Since 2001, buoyed by increasing numbers of tourists, the city council has promoted a number of cultural quarters.

The Cathedral Quarter comprises much of Belfast's old trade and warehousing district in the narrow streets and entries around St Anne's Cathedral, with a concentration of bars, beer gardens, clubs and restaurants (including two establishments claiming descent from the early town, White's and The Duke of York)[151] and performance spaces (most notably the Black Box and Oh Yeah).[152][153] It hosts a yearly visual and performing arts festival. The adjoining Custom House Square is one of the city's main outdoor venues for free concerts and street entertainment.

Without defined geographical boundaries, the Gaeltacht Quarter encompasses Irish-speaking Belfast. (According to the 2021 census, 15.5% of people in the city have some knowledge of Irish, 4% speak it daily).[154] It is generally understood as an area around the Falls Road in west Belfast served by the Cultúrlann McAdam Ó Fiaich cultural centre.[155][156] It can be said to include, at the Skainos Centre in unionist east Belfast, Turas, a project that promotes Irish through night classes and cultural events in the belief that "the language belongs to all".[157]

The Linen Quarter', an area south of City Hall once dominated by linen warehouses, now includes, in addition to cafés, bars and restaurants, a dozen hotels (including the 23-storey Grand Central Hotel), and the city's two principal Victorian-era cultural venues, the Grand Opera House and the Ulster Hall.[158]

Moving further south along the so-called "Golden Mile" of bars and clubs through Shaftesbury Square, there is the Queen's [University] Quarter. In addition to the university (spread over 250 buildings, of which 120 are listed as being of architectural merit),[159] it is home to Botanic Gardens and the Ulster Museum.[160]

Finally, the Titanic Quarter covers 0.75 km2 (185 acres) of reclaimed land adjacent to Belfast Harbour, formerly known as Queen's Island. Named after RMS Titanic, launched here in 1911,[161] work began in 2003 to transform some former shipyard land into "one of the largest waterfront developments in Europe".[162] The current area houses Titanic Belfast, the Public Records Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), two hotels, and multiple condo towers and shops, and the Titanic [film] Studios.[163]

Culture

[edit]Arts venues and festivals

[edit]From Georgian Belfast, the city retains a civic legacy. In addition to Clifton House[164] (Belfast Charitable Society, 1774), this includes the Linen Hall Library[165] (Belfast Society for Promoting Knowledge, 1788), the Ulster Museum (founded by the Belfast Natural History Society as the Belfast Municipal Museum and Art Gallery in 1833), and the Botanic Gardens[166] (established in 1828 by the Belfast Botanic and Horticultural Society).[166] These remain important cultural venues: in the case of the Gardens, for outdoor festivities including the Belfast Melā, the city's annual celebration of global cultures.[167]

Of the many stage venues built in the nineteenth century, and film theatres built in the twentieth, there remains the Ulster Hall (1862),[168] which hosts concerts (including those of the Ulster Orchestra), classical recitals and party-political meetings; the Grand Opera House[169] (1895) badly damaged in bomb blasts in the early 1990s, restored and enlarged 2020; the Strand Cinema[170] (1935) now being developed as an arts centre;[171] and the Queens Film Theatre (QFT) (1968) focussed on art house and world cinema.[172] The two independent cinemas offer their screens for the Belfast Film Festival and the Belfast International Arts Festival.

The principal stage for drama remains the Lyric Theatre (1951), the largest employer of actors and other theatre professionals in the region.[173] At Queens University, drama students stage their productions at the Brian Friel Theatre, a 120-seat studio space (named after the renowned playwright).[174]

In November 2011, Belfast became the smallest city to host the MTV Europe Music Awards.[175] The event was made possible by the 11,000-seat Odyssey Arena (today the SSE Arena) which opened in 2000 at the entrance to the Titanic Quarter[176] A further large-scale venue is the Waterfront Hall, a multi-purpose conference and entertainment centre that first opened in 1997. The main circular Auditorium seats 2,241 and is based on the Berlin Philharmonic Hall.[177] In 2012, the Metropolitan Arts Centre, usually referred to as the MAC, was opened in the Cathedral Quarter, offering a performance mix of music, theatre, dance and visual art.[178]

The city has a number of community arts, and arts education, centres, among them the Crescent Arts Centre[179] in south Belfast, the Irish-language Cultúrlann McAdam Ó Fiaich[180] in west Belfast, The Duncairn[181] in north Belfast and, in the east of the city, EastSide Arts.[182]

Féile an Phobail, a community arts organisation born out of the Internment Commemorations in the west of the city, stages one of the largest community festivals in Europe.[183] It has grown from its original August Féile on the Falls Road, to a year-round programme with a broad range of arts events, talks and discussions.[184]

UNESCO City of Music

[edit]In November 2021, Belfast became the third city in the British Isles to be designated by UNESCO as City of Music (after Glasgow in 2008 and Liverpool in 2016) and is one of 59 cities worldwide participating in the UNESCO Creative Cities Network.[185][186]

The greater part of Belfast's music scene is accommodated in the city's pubs and clubs. Irish traditional music ("trad") is a staple, and is supported, along with Ulster-Scots snare drum and pipe music, by the city's TradFest summer school.[187][188]

Music offerings also draw on the legacy of the punk[189] and the underground club scene that developed during The Troubles[190] (associated with the groups Stiff Little Fingers and The Undertones, and celebrated in the award-winning 2013 film, Good Vibrations).[191] Snow Patrol's frontman Gary Lightbody led a line up of private donors that together with public funders established the Oh Yeah music centre in 2008.[192] The Cathedral Quarter non-profit supports young musicians and these have engaged with a range of genres including Alternative rock, Indie rock, Electronica, Post rock, Post punk, Crossover, and Experimental rock.

Queens University hosts the Sonic Arts Research Centre (SARC), an institute for music-based practice and research. Its purpose designed building, Sonic Laboratory and multichannel studios were opened by Karlheinz Stockhausen, the German composer and "father of electronic music",[193][194] in 2004.[195]

Media

[edit]

Belfast is the home of the Belfast Telegraph, Irish News, and The News Letter, the oldest English-language daily newspaper in the world still in publication.[196][197]

The city is the headquarters of BBC Northern Ireland, and ITV station UTV. The Irish public service broadcaster, RTÉ has a studio in the city.[198] The national radio station is BBC Radio Ulster with commercial radio stations such as Q Radio, U105, Blast 106 and Irish-language station Raidió Fáilte. Queen's Radio, a student-run radio station broadcasts from Queen's University Students' Union.

One of Northern Ireland's two community TV stations, NvTv, is based in the Cathedral Quarter of the city. Broadcasting only over the Internet is Homely Planet, the Cultural Radio Station for Northern Ireland, supporting community relations.[199]

Parades

[edit]Since the lifting in 1872 of a twenty-year party processions ban, Orange parades in celebration of "the Twelfth" [of July] and the bonfires of the previous evening, the eleventh, have been a fixed fixture of the Belfast calendar.[200] On what became a public holiday in 1926,[201] Belfast and guest Orange lodges with their pipe, flute and drum bands muster at Carlisle Circus, and parade through the city centre past the City Hall and out the Lisburn Road to a gathering in "the field" at Barnett Demesne.[202] While some local feeder and return marches have a history of sectarian disturbance, in recent years, events have generally passed off without serious incident.[203]

In 2015, the Orange Order opened the Museum of Orange Heritage on the Cregagh Road in East Belfast with the aim of educating the wider public about "the origins, traditions and continued relevance" of the parading institution.[204]

What is sometimes referred to as the Catholic equivalent of the Orangemen,[205] the much smaller Ancient Order of Hibernians, confines its parades to nationalist areas in west and north Belfast,[206] as do republicans commemorating the Easter Rising.[207] In August 1993, in a break with a history of nationalist exclusion from the city centre, a parade marking the introduction of internment in the 1971 proceeded up Royal Avenue toward the City Hall, where it was addressed by Sinn Féin president, Gerry Adams, in front of the statue of Queen Victoria.[208]

Since 1998, the Belfast City Council has funded a city-centre St. Patrick's Day (March 17) celebration. It is organised by Féile an Phobail as a "carnival" complete with a parade featuring dancers, circus entertainers, floats, and giant puppets.[209] Critical of what they perceive as an evolving nationalist festival, unionists on the City Council observe that "a lot of the Protestant Unionist Loyalist (PUL) community will stay away from the city centre on St Patrick's Day, the same as some stay away on the Twelfth of July".[210]

In 1991, Belfast hosted its first gay pride event. Belfast Pride, culminating in a city-centre parade at the end of July, is now one of the biggest annual festivals in the city and, according to its organisers, the largest LGBT+ festival in Ireland.[211][212]

The Irish Congress of Trade Unions organises an annual city-centre May Day march and rally.[213] The International Workers Day has been a public holiday since 1978.[214]

Demography

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1757 | 8,549 | — |

| 1782 | 13,105 | +1.72% |

| 1791 | 18,320 | +3.79% |

| 1806 | 22,095 | +1.26% |

| 1821 | 37,277 | +3.55% |

| 1831 | 53,287 | +3.64% |

| 1841 | 75,308 | +3.52% |

| 1851 | 97,784 | +2.65% |

| 1861 | 119,393 | +2.02% |

| 1871 | 174,412 | +3.86% |

| 1881 | 208,122 | +1.78% |

| 1891 | 255,950 | +2.09% |

| 1901 | 349,180 | +3.15% |

| 1911 | 386,947 | +1.03% |

| 1926 | 415,151 | +0.47% |

| 1937 | 438,086 | +0.49% |

| 1951 | 443,671 | +0.09% |

| 1961 | 415,856 | −0.65% |

| 1966 | 398,405 | −0.85% |

| 1971 | 362,082 | −1.89% |

| 1981 | 314,270 | −1.41% |

| 1991 | 279,237 | −1.17% |

| 2001 | 277,391 | −0.07% |

| 2006 | 267,374 | −0.73% |

| 2011 | 280,138 | +0.94% |

| 2021 | 293,298 | +0.46% |

| 2021 figure is for the city within its pre-2015 local government boundaries.[215][216][217][218][219][220][221][222] | ||

In 2021, there were 345,418 residents within the expanded 2015 Belfast local government boundary[223] and 634,600 in the Belfast Metropolitan Area,[224] approximately one third of Northern Ireland's 1.9 million population.

As with many cities, Belfast's inner city is currently characterised by the elderly, students and single young people, while families tend to live on the periphery. Socio-economic areas radiate out from the Central Business District, with a pronounced wedge of affluence extending out the Malone Road and Upper Malone Road to the south.[225] Deprivation levels are notable in the inner parts of the north and the west of the city. The areas around the Falls Road, Ardoyne and New Lodge (Catholic nationalist) and the Shankill Road (Protestant loyalist) experience some of the highest levels of social deprivation including higher levels of ill health and poor access to services. These areas remain firmly segregated, with 80 to 90 percent of residents being of the one religious designation.[226][227]

Consistent with the trend across all of Northern Ireland, the Protestant population within the city has been in decline, while the non-religious, other religious and Catholic population has risen. The 2021 census recorded the following: 43% of residents as Catholic, 12% as Presbyterian, 8% as Church of Ireland, 3% as Methodist, 6% as belonging to other Christian denominations, 3% to other religions and 24% as having either no religion or no declared religion.[154]

In terms of community background, 47.93% were deemed to belong to, or to have been brought up in, the Catholic faith and 36.45% in a Protestant or other Christian-related denomination.[228] The comparable figures in 2011 were 48.60% Catholic and 42.28% Protestant or other Christian-related denomination.[229]

With respondents free to indicate more than one national identity, in 2021 the largest national identity group was "Irish only" with 35% of the population, followed by "British only" 27%, "Northern Irish only" 17%, "British and Northern Irish only" 7%, "Irish and Northern Irish only" 2%, "British, Irish and Northern Irish only" 2%, British and Irish less than 1% and Other identities with 10%.[154]

Insofar as the city's two indigenous minority languages (Irish and Ulster Scots) are concerned, figures are made available from the decennial UK census. On census day, 21 March 2021, 14.93% (43,798) in Belfast claimed to have some knowledge of the Irish language, whilst 5.21% (15,294) claimed to be able to speak, read, write and understand spoken Irish.[230] 3.74% (10,963) of residents claimed to use Irish daily and 0.75% (2,192) claimed Irish is their main language.[231][232] 7.17% (21,025) of people in the city claimed to have some knowledge of Ulster Scots, whilst 0.75% (2,207) claimed to be able to speak, read, write and understand spoken Ulster Scots.[233] 0.83% (2,430) claimed to use Ulster Scots daily.[234]

From the mid to late 19th century, there was a community of central European Jews[235] (among its distinguished members, Hamburg-born Gustav Wilhelm Wolff of Harland & Wolff)[236] and of Italians[237] in Belfast.[238] Today, the largest immigrant groups are Poles, Chinese and Indians.[239][240] The 2011 census figures recorded a total non-white population of 10,219 or 3.3%,[240] while 18,420 or 6.6%[239] of the population were born outside the UK and Ireland.[239] Almost half of those born outside the British Isles lived in south Belfast, where they comprised 9.5% of the population.[239] The majority of the estimated 5,000 Muslims[241] and 200 Hindu families[242] living in Northern Ireland resided in the Greater Belfast area. In the 2021 census the percentage of the city's residents born outside the United Kingdom had risen to 9.8.[84]

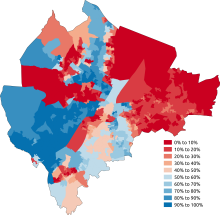

- The Belfast City Council area in the 2011 census

-

Percentage Catholic or brought up Catholic

-

Most commonly stated national identity

-

Percentage born outside the UK and Ireland

Economy

[edit]

Employment profile

[edit]Services (including retail, health, professional & scientific) account for three quarters of jobs in Belfast. Only 6% remain in manufacturing. The balance is in distribution and construction.[243] In recent years, unemployment has been comparatively low (under 3% in the summer of 2023) for the UK. On the other hand, Belfast has a high rate of people economically inactive (close to 30%).[244] It is a group, encompassing homemakers, full-time carers, students and retirees,[245] that in Belfast has been swollen by the exceptionally large proportion of the population (27%) with long-term health problems or disabilities[246] (and who, in Northern Ireland generally, are less likely to be employed than in other UK regions).[247]

Shipbuilding, aerospace and defence

[edit]Of Belfast's Victorian-era industry, little remains. The last working linen factory—Copeland Linens Limited, based in the Shankill area—closed in 2013.[248] In recent years Harland & Wolff, which at peak production in the Second World War had employed around 35,000 people, has had a workforce of no more than two or three hundred refurbishing oil rigs and fabricating off-shore wind turbines. A £1.6 billion Royal Navy contract has offered the yard a new lease, returning it to shipbuilding in 2025.[32]: 261–262 [249]

In 1936, Short & Harland Ltd, a joint venture of Short Brothers and Harland & Wolff, began the manufacture of aircraft in the docks area. In 1989, the British government, which had nationalised the company during the Second World War, sold it to the Canadian aerospace company Bombardier. In 2020, it was sold on to Spirit AeroSystems.[250] Producing aircraft components, it remains the largest manufacturing concern in Northern Ireland.[251]

Originating in the Short Brothers' missile division, since 2001 Thales Group[252] owned Thales Air Defence Limited[253] has been producing short range air defence and anti-tank missiles[254] (including the NLAW shoulder-launched system deployed against the Russian invasion by Ukraine).[255]

Fintech and cybersecurity

[edit]From the 1990s, Belfast established itself as a significant location for call centres and for other back-office services.[256] Attracting U.S. operators such as Citi, Allstate, Liberty Mutual, Aflac and FD Technologies (Kx Systems),[257] it as since been identified by the UK Treasury as "key fintech [financial technology] hub".[258] Fintech's key areas (its "ABCD") are artificial intelligence, blockchain, cloud computing, and big data.[259]

The sector's principal constraint, cyber security, has been addressed since 2004 by the Queens University Institute of Electronics, Communications and Information Technology (IECIT), and its Centre for Secure Information Technologies (CSIT).[260] The IECIT is the anchor tenant at Catalyst (science park)[261] in the Titanic Quarter, which hosts a cluster of companies seeking to offer innovative cyber-security solutions.[262]

Film

[edit]Between 2018 and 2023, film and television production based largely in Belfast, and occupying significant new studio capacity in the ports area, contributed £330m to Northern Ireland's economy.[263] There are two 8-acre media complexes (serviced by the adjacent City Airport): the Titanic Studios on Queen's Island (the Titanic Quarter) and across the Victoria Channel in Giant's Park on the Lough's north foreshore, the Belfast Harbour Studios.[264] Together they offer 226,000 ft2 of studio space, plus offices and workshops,[265] and have attracted U.S. production companies such as Amazon, HBO (including all eight series of its fantasy drama Game of Thrones), Paramount, Playtone, Universal, and Warner Bros.[266][264]

At the beginning of 2024, Ulster University, in partnership with Belfast Harbour and supported by Northern Ireland Screen, announced an £72m investment to add to the complex a new virtual production, research and development, facility, Studio Ulster.[267][268] Additional studio space is available at Loop Studios (formerly Britvic) on the Castlereagh Road in East Belfast.[265][269]

Tourism and hospitality

[edit]Northern Ireland's peace dividend since the 1990s, which includes a marked increase in inward investment,[270][271] has contributed to a large-scale redevelopment of the city centre. Significant projects included Victoria Square, the Cathedral Quarter, Laganside with the Odyssey complex and the landmark Waterfront Hall, the new Titanic Quarter with its Titanic Belfast visitor attraction, and the development of the original Short's harbour airfield as George Best Belfast City Airport. These developments reflect a boom in tourism (32 million visitors between 2011 and 2018),[32]: 179 and related hotel construction. This has included an entirely new phenomenon for Belfast: in 1999, the port received its first cruise ship.[272] In 2023, Belfast welcomed 153 calls, 8% up from the pre-pandemic record set in 2019. Ship from 32 different countries landed 320,000 passengers.[273]

Belfast has also seen growth of "conflict tourism".[32]: 186–191 To the dismay of some, "tourists take photos of the division lines that are not consigned to history, but are a part of living Belfast: children play football against the walls that tourists flock to. The places and the people themselves have become a spectacle, an attraction."[274] Tourist bosses and guides, however, are satisfied that the greater draw is city's other "must-see attractions",[275] and its "convivial food and nightlife scene".[276]

EU/GB Trade

[edit]Invest NI, Northern Ireland's economic development agency is pitching Belfast and its hinterland to foreign investors as "only region in the world able to trade goods freely with both GB and EU markets".[277] This follows the 2020 Northern Ireland Protocol and the 2023 Windsor Framework, agreements between the British government and European Union, whereby, post-Brexit, Northern Ireland would effectively remain within the European Single Market for goods while, in principle, retaining unfettered access to the British domestic market. Despite the DUP's derailment of devolved government in protest, local business leaders largely welcomed the new trade regime, hailing the promise of dual EU-GB access as a critical opportunity.[278][279]

In February 2024, the DUP consented to a return of the devolved Assembly and Executive on the understanding that neither the EU nor the British government would defend the integrity of their respective internal markets by conducting routine checks on the bulk of goods passing through Belfast, or other Northern Ireland, ports.[280]

Education

[edit]Primary and secondary education

[edit]Children from Catholic and Protestant homes in Belfast are taught, for the most part, separately on a pattern that, by the mid-nineteenth century, had been established throughout Ireland.[281] Primary and secondary education is divided between (Catholic) Maintained Schools and (non-Catholic/ "Protestant") Controlled Schools.[282] They are bound by the same curriculum, but their teaching staff are trained separately (in the university colleges of St Mary's and Stranmillis).[283][284]: 200–202

Since the 1980s, two smaller school sectors have emerged: grant-maintained Integrated schools, which by design bring together children and staff from both communities, and Irish language medium schools[282]

The Belfast [later Royal Belfast] Academical Institution, opened its doors in 1810 with the intention, in the words of its founder, former United Irishman, William Drennan of being "perfectly unbiased by religious distinctions".[285] The principle was not embraced by the town's middle-classes: in practice "Inst" provided a grammar education to the town's Presbyterian families while Anglicans favoured the older Royal Belfast Academy (1785); Catholics, St Malachy's diocesan college (1833) and Wesleyans, Methodist College Belfast (1865).

Denominational lines have since blurred, with Catholics in particular moving into the controlled grammars.[286] But the presence of 18 selective grammar schools in Belfast is a further feature of post-primary education in Belfast that distinguishes it from that of comparable cities in Great Britain where academic selection was abandoned in the 1960s and 70s.[287] Partly prompted by the COVID disruption of external testing in 2021/22,[288] some the city's grammars have begun to review and amend the practice. It is not clear that this will be on terms that reduce the degree of social segregation they have represented within the system.[289]

In 2006, the Belfast Education and Library Board became part of the consolidated Education Authority for Northern Ireland. In Belfast, the Authority has responsibility for 156 primary,[290] and 48 secondary schools (including the 18 grammars).[291] The system is marked by stark inequalities in outcome.[292] Around 30% of school leavers in the city do not attain 5 GCSEs, A* - C (including Maths and English). For those in receipt of free school meals, the figure rises to over 50%.[293]

Further and Higher education

[edit]Belfast Metropolitan College ("Belfast Met") is a further education college with three main campuses around the city, including several smaller buildings. Formerly known as Belfast Institute of Further and Higher Education, it specialises in vocational education. The college has over 53,000 students enrolled on full-time and part-time courses, making it one of the largest further education colleges in the UK and the largest in the island of Ireland.[294]

Belfast has two universities. Queen's University Belfast was founded as a college in 1845. In 1908, the Catholic bishops lifted their ban on attendance and Queen's was granted university status.[284]: 164, 166 It is a member of the Russell Group, an association of 24 leading research-intensive universities in the UK,[295] and is one of the largest universities in the UK with over 25,000 students – among them over 4,000 international students.[296]

Ulster University, created in its current form in 1984, is a multi-centre university with a campus on the edge of the Cathedral Quarter of Belfast. Since 2021, this original "Arts College" campus has undergone a £1.4bn expansion to accommodate offerings across all departments. The project promises to bring 15,500 staff and students into the city, and to generate 5,000 new jobs.[297][298]

Governance

[edit]Belfast was granted borough status by James VI and I in 1613 and official city status by Queen Victoria in 1888.[299] Since 1973 it has been a local government district under local administration by Belfast City Council.[300]

Belfast has been represented in the British House of Commons since 1801, and in Northern Ireland Assembly, as presently constituted, since 1998.

Local government

[edit]Belfast City Council is responsible for a range of powers and services, including land-use and community planning, parks and recreation, building control, arts and cultural heritage.[301] The city's principal offices are those of the Lord Mayor of Belfast, Deputy Lord Mayor and High Sheriff. Like other elected positions within the Council such as Committee chairs, these are filled since 1998 using the D'Hondt system so that in recent years the position has rotated between councillors from the three largest factions, Sinn Féin, the DUP and the Alliance Party.

The first Lord Mayor of Belfast in 1892, Daniel Dixon, like every mayor but one until 1997 (Alliance in 1979), was a unionist.[302] The first nationalist Lord Mayor of Belfast was Alban Maginness of the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) in 1997. The current Lord Mayor is Micky Murray of the Alliance Party of Northern Ireland, who has been in the position of Lord Mayor since 3 June 2024. His duties include presiding over meetings of the council, receiving distinguished visitors to the city, representing and promoting the city on the national and international stage.[302]

In 1997, unionists lost overall control of Belfast City Council for the first time in its history, with the Alliance Party holding the balance of power. In 2023, unionists retained just 17 of 60 seats on the council, leaving nationalists (Sinn Féin and the SDLP) just 4 seats short of a majority.[303] In addition to the 11 Alliance members there are four other councillors, 3 Green and 1 People Before Profit, who refuse a nationalist/unionist designation.

Northern Ireland Assembly and Westminster elections

[edit]As Northern Ireland's capital city, Belfast is host to the Northern Ireland Assembly at Stormont, the site of the devolved legislature for Northern Ireland. Belfast is divided into four Northern Ireland Assembly and UK parliamentary constituencies: Belfast North, Belfast West, Belfast South and Mid Down and Belfast East. All four extend beyond the city boundaries to include parts of Antrim and Newtownabbey and Lisburn and Castlereagh districts. In United Kingdom elections, each constituency returns one MP, on a "first past the post" basis to Westminster. In NI Assembly elections each returns, on the basis of proportional representation, five MLAs to Stormont.

In the Northern Ireland Assembly Elections in 2022, Belfast elected 7 Sinn Féin, 5 DUP, 5 Alliance Party, 1 SDLP, 1 UUP and 1 PBPA MLAs.[304] In the 2017 UK general election, the DUP won all but the Sinn Féin stronghold of Belfast West. In the 2019 and 2024 UK general elections, they retained only Belfast East, losing Belfast North to Sinn Féin and Belfast South to the SDLP.

Infrastructure

[edit]Hospitals

[edit]The Belfast Health & Social Care Trust is one of five trusts that were created on 1 April 2007 by the Department of Health. Belfast contains most of Northern Ireland's regional specialist centres.[305]

The Royal Hospitals site in west Belfast (junction of Grosvenor and Falls roads) contains two hospitals. The Royal Victoria Hospital (its origins in a number of successive institutions, beginning in 1797 with The Belfast Fever Hospital)[306] provides both local and regional services. Specialist services include cardiac surgery, critical care and the Regional Trauma Centre.[307] The Children's Hospital (Royal Belfast Hospital for Sick Children) provides general hospital care for children in Belfast and provides most of the paediatric regional specialities.[308]

The Belfast City Hospital (evolved from Belfast Union Workhouse and infirmary)[309] on the Lisburn Road is the regional specialist centre for haematology and is home to a major cancer centre.[310] The Mary G McGeown Regional Nephrology Unit at the City Hospital is the kidney transplant centre and provides regional renal services for Northern Ireland.[311] Musgrave Park Hospital in south Belfast specialises in orthopaedics, rheumatology, sports medicine and rehabilitation. It is home to Northern Ireland's first Acquired Brain Injury Unit.[312]

The Mater Hospital (founded in 1883 by the Sisters of Mercy)[313] on the Crumlin Road provides a wide range of services, including acute inpatient, emergency and maternity services, to north Belfast and the surrounding areas.[314]

The Ulster Hospital, Upper Newtownards Road, Dundonald, on the eastern edge of the city, first founded as the Ulster Hospital for Women and Sick Children in 1872,[315] is the major acute hospital for the South Eastern Health and Social Care Trust. It delivers a full range of outpatient, inpatient and daycare medical and surgical services.[316]

Transport

[edit]

Belfast is a relatively car-dependent city by European standards, with an extensive road network including the 22.5 miles (36 km) M2 and M22 motorway route.[317]

Black taxis are common in the city, operating on a share basis in some areas.[318] These are outnumbered by private hire taxis. Bus and rail public transport in Northern Ireland is operated by subsidiaries of Translink. Bus services in the city proper and the nearer suburbs are operated by Translink Metro, with services focusing on linking residential districts with the city centre on 12 quality bus corridors running along main radial roads,[319]

More distant suburbs are served by Ulsterbus. Northern Ireland Railways provides suburban services along three lines running through Belfast's northern suburbs to Carrickfergus, Larne and Larne Harbour, eastwards towards Bangor and south-westwards towards Lisburn and Portadown. This service is known as the Belfast Suburban Rail system. Belfast is linked directly to Coleraine, Portrush and Derry. Belfast has a direct rail connection with Dublin called Enterprise operated jointly by NIR and the Irish rail company Iarnród Éireann.

In 2024, the city's Europa Bus Centre and Great Victoria Street rail station, was replaced by a new Belfast Central Station. It is "the largest integrated transport facility on the island of Ireland" with bus stands, railway platforms, and facilities for taxis and bicycles.[320]

The city has two airports: George Best Belfast City Airport, close to the city centre on the eastern shore of Belfast Lough and Belfast International Airport 30–40 minutes to the west on the shore of Lough Neagh. Both operate UK domestic and European flights. The city is also served by Dublin Airport, two hours to the south, with direct inter-continental connections.

In addition to its extensive freight business, the Belfast Port offers car-ferry sailings, operated by Stena Line, to Cairnryan in Scotland (5 Sailings Daily. 2 hours 22 minutes) and to Liverpool-Birkenhead (14 sailings weekly. 8 hours). The Isle of Man Steam Packet Company provides a seasonal connection to Douglas, Isle of Man.

The Glider bus service is a new form of transport in Belfast. Introduced in 2018, it is a bus rapid transit system linking East Belfast, West Belfast and the Titanic Quarter from the City Centre.[321] Using articulated buses, the £90 million service saw a 17% increase in its first month in Belfast, with 30,000 more people using the Gliders every week. The service is being recognised as helping to modernise the city's public transport.[322]

National Cycle Route 9 to Newry,[323] which will eventually connect with Dublin,[324] starts in Belfast.

Utilities

[edit]

Half of Belfast's water is supplied via the Aquarius pipeline from the Silent Valley Reservoir in County Down, created to collect water from the Mourne Mountains.[325] The other half is now supplied from Lough Neagh via Dunore Water Treatment Works in County Antrim.[326][327] The citizens of Belfast pay for their water in their rates bill. Plans to bring in additional water tariffs were deferred by devolution in May 2007.[328]

Power is provided from a number of power stations via NIE Networks Limited transmission lines. (Just under a half of electricity consumption in Northern Ireland is generated from renewable sources).[329] Phoenix Natural Gas Ltd. started supplying customers in Larne and Greater Belfast with natural gas in 1996 via the newly constructed Scotland-Northern Ireland pipeline.[326] Rates in Belfast (and the rest of Northern Ireland) were reformed in April 2007. The discrete capital value system means rates bills are determined by the capital value of each domestic property as assessed by the Valuation and Lands Agency.[330]

Recreation and sports

[edit]Leisure centres

[edit]Belfast City Council owns and maintains 17 leisure centres across the city, run on its behalf by the non-profit social enterprise GLL under the 'Better' brand.[331] These include eight large multipurposed centres complete with swimming pools: Ballysillan Leisure Centre and Grove Wellbeing Centre in North Belfast; the Andersonstown, Falls, Shankill and Whiterock leisure centres in West Belfast; Templemore Baths and Lisnasharragh Leisure Centre in East Belfast, and close to the city centre in South Belfast, the Olympia Leisure Centre and Spa,[332]

Parks and gardens

[edit]Belfast has over forty parks. The oldest (1828) and one of the most popular parks Botanic Gardens[333] in the Queen's Quarter. Built in the 1830s and designed by Sir Charles Lanyon, its Palm House is one of the earliest examples of a curvilinear and cast iron glasshouse.[334] Other attractions in the park include the recently restored Tropical Ravine, a humid jungle glen built in 1889,[335] rose gardens and public events ranging from live opera broadcasts to pop concerts.[336]

The largest municipal park in the city, and closest to the city centre, lies on the right bank of Lagan. The 100-acres of Ormeau Park were opened to the public in 1871 on what was the last demesne of the town's former proprietors, the Chichesters, Marquesses of Donegall.[337]

In north Belfast, the Waterworks, two reservoirs to which the public have had access since 1897, are features of a park supporting angling and waterfowl.[338] In 1906, a further water park, Victoria, opened behind industrial dockland on what had been the eastern shore of the Lough.[339] It is now connected through east Belfast by the Connswater Community Greenway which offers 16 km of continuous cycle and walkway through east Belfast.[340]

The largest green conservation area within the city's boundaries is a 2,116 hectares patchwork of "parks, demesnes, woodland and meadows" stretching upriver along the banks of the Lagan river and canal;[117] Established in 1967, the Lagan Valley Regional Park envelopes in its course, Belvoir Park Forest, which contains ancient oaks and a 12th-century Norman Motte,[341] and Sir Thomas and Lady Dixon Park, whose International Rose Garden attracts thousands of visitors each July.[342]

Colin Glenn Forest Park,[343] the National Trust Divis and the Black Mountain Ridge Trail,[344] and Cave Hill Country Park.[345] offer panoramic views over Belfast and beyond from the west.[344] Climbing the Castlereagh Hills, the National Trust Lisnabreeny Cregagh Glen does the same from the east.[346]

Below Cave Hill, the council maintains one of the few local government-funded zoos in the British Isles. The Belfast Zoo houses more than 1,200 animals of 140 species including Asian elephants, Barbary lions, Malayan sun bears (one of the few in the United Kingdom), two species of penguin, a family of western lowland gorillas, a troop of common chimpanzees, a pair of red pandas, a pair of Goodfellow's tree-kangaroos and Francois' langurs. It carries out important conservation work and takes part in European and international breeding programmes which help to ensure the survival of many species under threat.[347]

Sports

[edit]

Belfast has several notable sports teams playing a diverse variety of sports such as football, Gaelic games, rugby, cricket, and ice hockey. The Belfast Marathon is run annually on May Day, The 41st Marathon in 2023, with related events (Wheelchair Race, Team Relay and 8 Mile Walk) attracted 15,000 participants.[348]

The Northern Ireland national football team plays its home matches at Windsor Park. Football clubs with stadia and training grounds in the city include: Linfield, Glentoran, Crusaders, Cliftonville, Donegal Celtic, Harland & Wolff Welders, Dundela, Knockbreda, PSNI, Newington, Sport & Leisure and Brantwood.[349]

Belfast is home to over twenty Gaelic football and hurling clubs.[350] Casement Park in west Belfast, home to the Antrim county teams, had a capacity of 31,500 making it the second largest Gaelic Athletic Association ground in Ulster.[351] Listed as one of the venues for the UK and Ireland's successful UEFA Euro 2028 bid, with co-funding from the Irish government there are plans for a complete rebuild.[352] In May 2020, the foundation of East Belfast GAA returned Gaelic Games to East Belfast after decades of its absence in the area. The current club president is Irish-language enthusiast Linda Ervine who comes from a unionist background in the area. The team currently plays in the Down Senior County League.[353]

The 1999 Heineken Cup champions Ulster Rugby play at Ravenhill Stadium in the south of the city. Belfast has four teams in rugby's All-Ireland League: Belfast Harlequins in Division 1B; and Instonians, Queen's University and Malone in Division 2A.

Belfast is home to the Stormont cricket ground since 1949 and was the venue for the Irish cricket team's first ever One Day International against England in 2006.[354]

The 9,500 capacity SSE Arena accommodates the Belfast Giants, one of the biggest ice hockey clubs in the UK. Featuring Canadian, ex-NHL players, the club competes the British Elite Ice Hockey League.

Belfast was the home town of former Manchester United player George Best, the 1968 European Footballer of the Year, who died in November 2005. On the day he was buried in the city, 100,000 people lined the route from his home on the Cregagh Road to Roselawn cemetery.[355] Since his death the City Airport was named after him and a trust has been set up to fund a memorial to him in the city centre.[356] Other sportspeople celebrated in the city include double world snooker champion Alex "Hurricane" Higgins[357] and world champion boxers Wayne McCullough, Rinty Monaghan and Carl Frampton.[358]

Climate

[edit]At 54°35′49″N 05°55′45″W / 54.59694°N 5.92917°W, its northern latitude is characterised by short winter days and long summer evenings. During the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year, local sunset is before 16:00 while sunrise is around 08:45. At the summer solstice in June, the sun sets after 22:00 and rises before 05:00.[359]

For this northern latitude, thanks to the influence of the Gulf Stream and North Atlantic Drift, Belfast has a comparatively mild climate. In summer the temperatures rarely range above 25 °C (77 °F) or dip in winter below −5 °C (23 °F).[360][361] The maritime influence, also ensures that the city gets significant precipitation. On 157 days in an average year, rainfall is greater than 1 mm. Average annual rainfall is 846 millimetres (33.3 in),[362] less than areas of northern England or most of Scotland,[363] but higher than Dublin or the south-east coast of Ireland.[364]

With its moderate temperatures and abundant rainfall, Belfast's climate is defined as a temperate oceanic climate (Cfb in the Köppen climate classification system), a classification it shares with most of northwest Europe.[365]

| Climate data for Belfast (Newforge),[b] elevation: 40 m (131 ft), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1982–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.0 (59.0) |

16.4 (61.5) |

19.7 (67.5) |

22.1 (71.8) |

25.4 (77.7) |

28.6 (83.5) |

30.2 (86.4) |

28.1 (82.6) |

23.7 (74.7) |

20.5 (68.9) |

17.1 (62.8) |

15.2 (59.4) |

30.2 (86.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8.2 (46.8) |

8.8 (47.8) |

10.5 (50.9) |

12.8 (55.0) |

15.7 (60.3) |

17.2 (63.0) |

19.7 (67.5) |

19.4 (66.9) |

17.3 (63.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

10.7 (51.3) |

8.4 (47.1) |

13.7 (56.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) |

5.5 (41.9) |

6.8 (44.2) |

8.8 (47.8) |

11.4 (52.5) |

14.0 (57.2) |

15.6 (60.1) |

15.4 (59.7) |

13.5 (56.3) |

10.4 (50.7) |

7.4 (45.3) |

5.4 (41.7) |

9.9 (49.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.2 (36.0) |

2.1 (35.8) |

3.1 (37.6) |

4.7 (40.5) |

7.0 (44.6) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.6 (52.9) |

11.5 (52.7) |

9.6 (49.3) |

6.9 (44.4) |

4.2 (39.6) |

2.3 (36.1) |

6.3 (43.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10.1 (13.8) |

−7.1 (19.2) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

1.3 (34.3) |

4.2 (39.6) |

2.5 (36.5) |

0.8 (33.4) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−13.5 (7.7) |

−13.5 (7.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 88.5 (3.48) |

70.3 (2.77) |

71.4 (2.81) |

60.4 (2.38) |

59.6 (2.35) |

69.0 (2.72) |

73.6 (2.90) |

85.0 (3.35) |

69.6 (2.74) |

95.8 (3.77) |

102.3 (4.03) |

93.3 (3.67) |

938.7 (36.96) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 14.4 | 12.7 | 12.6 | 11.3 | 11.5 | 11.4 | 13.0 | 13.5 | 11.6 | 13.8 | 15.5 | 14.8 | 156.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 40.1 | 65.2 | 97.7 | 157.1 | 185.1 | 151.1 | 146.3 | 141.9 | 112.0 | 92.4 | 52.9 | 35.3 | 1,277 |

| Source 1: Met Office[366] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Starlings Roost Weather[367][368] | |||||||||||||

In fiction

[edit]- John Greer Ervine, The Wayward Man (1927)

- F. L. Green, Odd Man Out (1945), basis of Odd Man Out, a 1947 British film noir directed by Carol Reed, and starring James Mason, Robert Newton.

- Brian Moore, The Emperor of Ice Cream (1965).

- Maurice Leitch, Silver's City (1981)

- Bernard MacLaverty, Cal (1983)

- Robert McLiam Wilson, Eureka Street (1996)

- Lucy Caldwell, Where They Were Missed (2005)

- Anna Burns, Milkman (2018)

- Louise Kennedy, Trespasses (2022)

- Michael Magee, Close to Home (2023)

Notable people

[edit]Georgian Belfast

[edit]- Edward Bunting (1773–1843), Irish folklorist, organiser of the 1792 Belfast Harp Festival

- Henry Cooke (1788–1868), Presbyterian Moderator, evangelist, proponent of "Protestant unity", commemorated in Cooke Memorial Church, May Street, and by the "Black Man" statue in College Square East

- Waddell Cunningham (1729–1797) Trans-Atlantic trader, West-Indian slaveholder, Irish Volunteer, liberal patron

- William Drennan (1754–1820), United Irishman, founder of the Royal Belfast Academical Institution (RBAI)

- Mary Ann McCracken (1766–1866) United Irishwoman, social activist, abolitionist, sister of Henry Joy McCracken hanged 1798, statue at City Hall

- James MacDonnell (1763–1845), physician, polymath patron of institutions since developed as the Royal Victoria Hospital, RBAI and the Linen Hall Library

- Martha McTier (1742–1837), United Irishwoman, advocate for women's health and education

- David Manson, (1726–1792), schoolmaster, pioneer of play and peer tutoring. Freedom of the Borough 1779

- Samuel Neilson (1761–1803) woollen merchant, publisher of the Northern Star, United Irishman

- John Templeton (1766–1825), "Father of Irish Botany", patron of the town's scientific and literary societies

Victorian Belfast

[edit]- Thomas Andrews (1873–1912), chief naval architect at Harland & Wolff, went down with RMS Titanic

- Joseph Biggar (1828–1890),"obstructionist" Irish nationalist MP, women's suffragist

- Margaret Byers (1832–1912), educator, activist, social reformer, missionary, founder of Victoria College